Main points

Main points

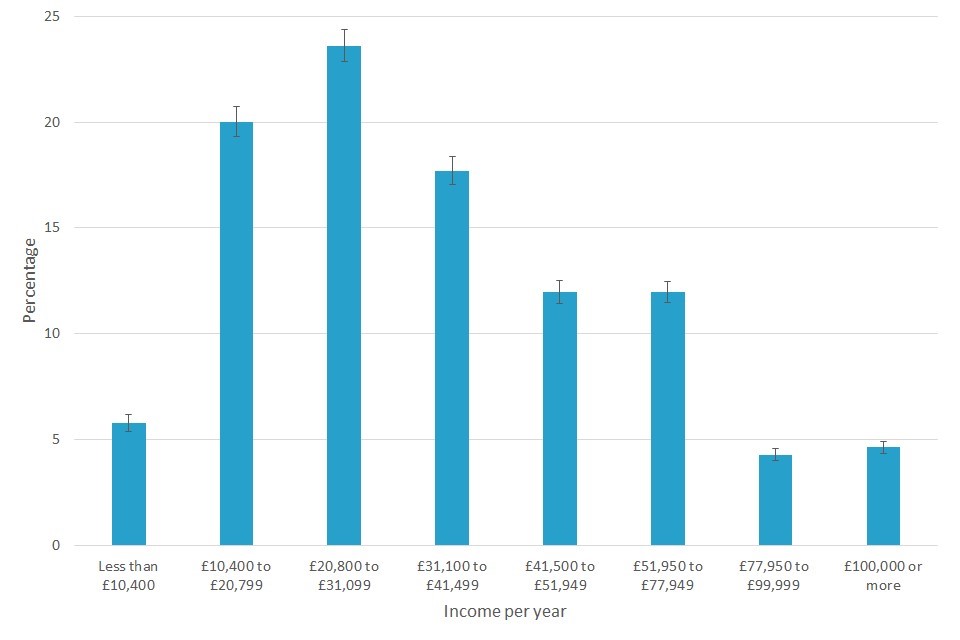

Among UK veterans who provided their gross personal income, 5.8% said their income was less than £10,400 a year, 43.6% said their income was between £10,400 and £31,099 a year, 29.7% said their income was between £31,100 and £51,949 a year, 16.3% said their income was between £51,950 and £99,999, and the remaining 4.6% said their income was £100,000 a year or more.

The survey attracted a higher proportion of veterans with a disability than we would expect of the veteran population, based on estimates from Census 2021; disability has a known relationship with income, and when we consider those who were disabled, 7.9% said their income was £10,400 a year or less, compared with 3.7% of veterans that were not disabled.

Just over half (50.1%) of veterans disagreed to some extent and nearly a third (30.5%) agreed to some extent with the statement “In the last month I have had money worries”. This aligns with comparable data sources that have reported on anxiety or worry around finances among UK adults.

Around 1 in 400 (0.3%) veterans said they were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse, and 9 in 400 (2.3%) said they lived long-term with family or friends.

Just over 1 in 10 (10.8%) veterans that were homeless or rough sleeping said they had received government support, such as from Veterans UK or local councils; just over 1 in 20 (5.7%) veterans that were homeless or rough sleeping said they had received support from charities, such as Citizens Advice, Shelter or SPACES, to help with housing.

Qualitative responses from veterans that had been homeless or rough sleeping in this article give more depth and context to how veterans feel they could have been better supported.

About the Veterans’ Survey 2022

These statistics are official statistics in development. They are published as research and are not official statistics.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published initial research on the Veterans’ Survey 2022 in its Veterans’ Survey 2022, demographic overview and coverage analysis article in December 2023. Aggregate analysis of the Veterans’ Survey will better represent veterans that have ever served as regulars because there was an under-representation of reserve veterans. This is shown by coverage analysis of veteran respondents from England and Wales, compared with veterans from Census 2021. Veterans with a disability were over-represented. There was a small under-representation of those that identified in all but the high-level White ethnic group. There was also an under-representation of veterans aged 75 years and over, which we have mitigated by weighting by age.

We only refer to a difference throughout this article where we are confident this difference is a statistically significant difference. This is based on the associated 95% confidence intervals found in our accompanying datasets. This article focuses on UK-level data only. Additional UK-level data and an exploration of whether we see the same patterns at country-level, where analysis of this was possible, are found in footnotes in our accompanying datasets.

We have published themed analysis of the Veterans’ Survey throughout 2024, as outlined in Related links.

Caution is necessary in assuming findings are representative of the whole veteran population. The Veterans’ Survey 2022 has been partially weighted to compensate for known biases in age among respondents from England and Wales only. Some biases remain, as outlined in the Veterans’ Survey 2022, demographic overview and coverage analysis, UK: December 2023 article.

Finance: income and money worries

Finance: income and money worries

Among UK veterans, 10.3% preferred not to say what their gross income was and 1.8% did not know their income. Among those that gave an income band, 5.8% said their income was less than £10,400 a year. We know the Veterans’ Survey sample over-represented disabled veterans, compared with estimates of the actual veteran population from Census 2021 (48.5 % compared with 32.1%). This is described in the Office for National Statistics’s (ONS’s) Veterans’ Survey 2022, demographic overview and coverage analysis, UK: December 2023 article.

Disability also has a known relationship with income. Those with a disability typically have a lower income than those without a disability, for example, as reported in the ONS’s Disability pay gaps in the UK: 2014 to 2023 article. We would not expect aggregate income estimates from the survey to be reflective of the true veteran population. However, when we consider those who were disabled among UK veterans, 7.9% said their income was £10,400 a year or less, compared with 3.7% of veterans that were not disabled.

Figure 1: Almost 6% of veterans said their income was £10,400 a year or less

Weighted percentages of veteran responses by income, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Blank responses to this question were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

“Prefer not to say” and “Don’t know” are removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Around a quarter of veterans said their income was less than £20,799 a year and almost half said their income was £31,099 a year or less. Just under a third of veterans (29.7%) said their income was between £31,100 and £51,949 a year, 16.3% said their income was between £51,950 and £99,999, and the remaining 4.6% said their income was £100,000 or more a year.

When we consider income by personal characteristics and service-related factors, we have combined income categories in our accompanying dataset in a way that allows for robust analysis at the multivariate level.

Data about personal income for the veteran and general population are not comparable. This is because veterans are typically older and more likely male than the general population, as shown in the ONS’s Characteristics of UK armed forces veterans, England and Wales: Census 2021 article.

Both age and gender are related to personal income. Males have higher average incomes than females and income typically increases with age up to age 50 years, as outlined in HM Revenue and Customs Personal Incomes Statistics 2020 to 2021: Commentary. Income data for the general UK population comes from the Survey of Personal Incomes, which only includes those who could be liable for UK Income Tax and covers income that can be assessed for tax for each tax year. Income Tax is typically paid when income reaches a threshold of £12,570 per annum. Some statistics in development that consider adult personal incomes regardless of tax liability are available for England and Wales only for the financial year ending 2018 in the ONS’s Admin-based income statistics article. It should be noted these data are for a time period over 4 years earlier. Findings suggest a much higher proportion of the general population earned £10,400 a year or less, compared with the veteran population and the 50th percentile for income was lower for the general population than what we see in the Veterans’ Survey data.

All respondents that said they were completing the survey on their own behalf were asked: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the statement: “In the last month I have had money worries”.

Figure 2: The majority of veterans disagreed to some extent that they had money worries in the last month

Weighted percentages of veteran responses by level of agreement they had experienced money worries in the last month, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked if in the last month, they have had money worries.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Around 3 in 10 UK veterans agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the past month (11.8% strongly agreed and 18.7% agreed). It is important to note the Veterans’ Survey data collection took place during the cost of living crisis and this finding aligns with available research based on the general UK population. For example, more than one-third (34.0%) of UK adults had felt anxious about their personal financial situation in the past month, according to the Mental Health Foundation’s (MHF’s) article on Stress, anxiety and hopelessness over personal finances widespread across UK. These findings are based on data from a poll of 5,000 UK adults, carried out by Opinium on behalf of MHF in November 2022.

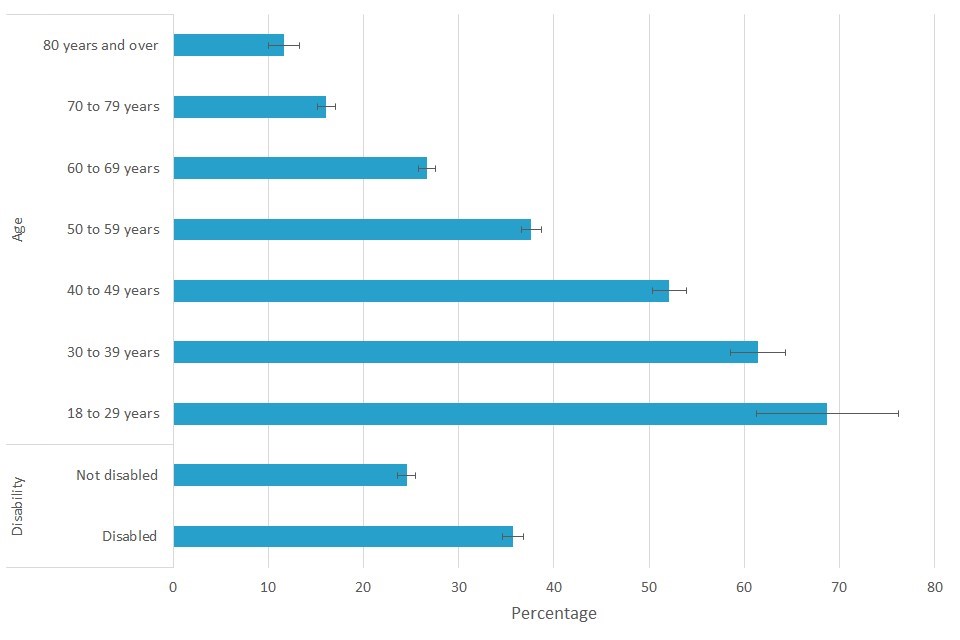

Figure 3: Agreement to some extent that a veteran had money worries in the last month was strongly associated with age and disability status

Weighted percentages of veterans that agreed to some extent they had experienced money worries in the last month by age and disability, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked if in the last month, they have had money worries.

This chart shows two separate variables, age and disability under the Equality Act 2010, which are derived from different questions.

“Age” refers to the age on the last birthday, rather than exact age.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Age had a strong linear relationship with how much UK veterans agreed that they had money worries in the last month. Those aged 80 years and over were least likely to agree to some extent and those aged 39 years or under were most likely to agree to some extent that they had money worries in the past month. There is evidence this relationship with age and financial well-being is also true of the general UK adult population, as detailed in the Money and Pensions Service’s Protected Characteristics and Financial Wellbeing An overview from the Financial Wellbeing Survey 2021 publication. We know the veteran population is older than the general population, so we would expect a lower proportion of veterans to agree that they had money worries than in the general population. However, we also have an over-representation in the sample of veterans with a disability. Among UK veterans, those that were disabled were more likely to have agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the past month, compared with those that were not disabled (35.7% compared with 24.5%).

We see similar patterns when we consider other health-related variables, such as requirements for a personalised care plan and whether a veteran left the UK armed forces because of medical discharge, compared with those that left for other reasons. For more information, see our accompanying dataset. For example, veterans that left the UK armed forces because of medical discharge were more likely to agree to some extent that they had money worries in the last month than those that left for any other reason, excluding those that preferred not to say why they left the UK armed forces.

We know responses to questions about money worries had a strong relationship with age. Many personal demographics are also associated with age. See our Life after service in the UK armed forces: Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK and Preparedness to leave the UK armed forces: Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK articles. Therefore, in this article, we focus on relationships between a personal characteristic or service-related factor and level of agreement that veterans had money worries in the last month that we expect to exist regardless of the age profile of veterans with that characteristic. This is based on additional age analysis detailed in our accompanying datasets.

Income did not have the same association with age as that seen for whether a veteran agreed to some extent they had money worries in the last month. The lowest income group we considered had high proportions of both the youngest (18 to 39 years old) and oldest (80 years and over) veterans within it. This is similar to the pattern for the general population reported through the Survey of Personal Incomes. Our accompanying dataset provides information for veteran responses to income and money worries by a broader range of personal demographics and service-related factors.

Income and money worries by other personal characteristics and service-related factors

Sex

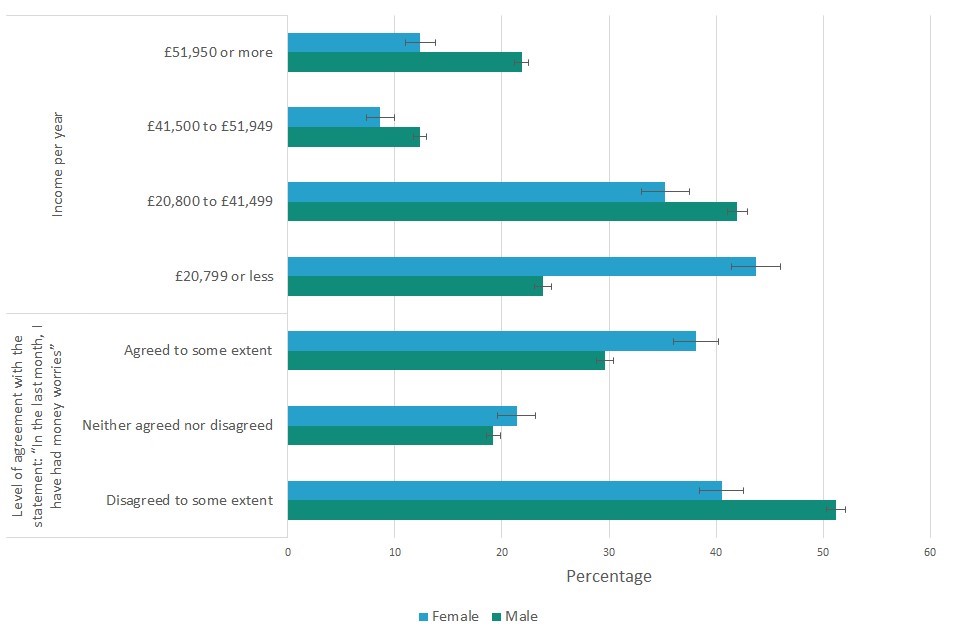

Finance data for the general population suggests women overall earn less than men and have lower financial well-being than men, as described in the Office for National Statistics’s (ONS’s) Gender pay gap in the UK: 2024 bulletin and in the Money and Pension Service’s (MPS’s) Protected Characteristics and Financial Wellbeing An overview from the Financial Wellbeing Survey 2021 publication. This was reflected in our findings among UK veterans.

Figure 4: Female veterans were more likely to earn £20,799 a year or less and less likely to earn £51,950 a year or more than male veterans, and were more likely to say they had money worries in the last month than male veterans

Weighted percentages of veteran responses about income and money worries in the last month by sex, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Blank responses and “Prefer not to say” responses were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked if in the last month, they have had money worries.

Personal Independence Payments and Adult Disability Payments are not means tested.

The income and extent of agreement with the statement “In the last month, I have had money worries” data are derived from different questions.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Sexual orientation

Evidence suggests that UK adults that identify as ‘LGB+ ’ tend to earn less and have lower financial well-being than those that identify as ‘straight or heterosexual’. This is detailed in the Pensions Regulator’s Diversity Pay Gap Report, 2023 and in MPS’s Protected Characteristics and Financial Wellbeing An overview from the Financial Wellbeing Survey 2021 publication.

There were similar findings among UK veterans. Those veterans that identified as straight or heterosexual were less likely than those that identified as LGB+ to have said their income was £20,799 a year or below. Those UK veterans that identified as straight or heterosexual were less likely than those that identified as LGB+ to have agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the past month.

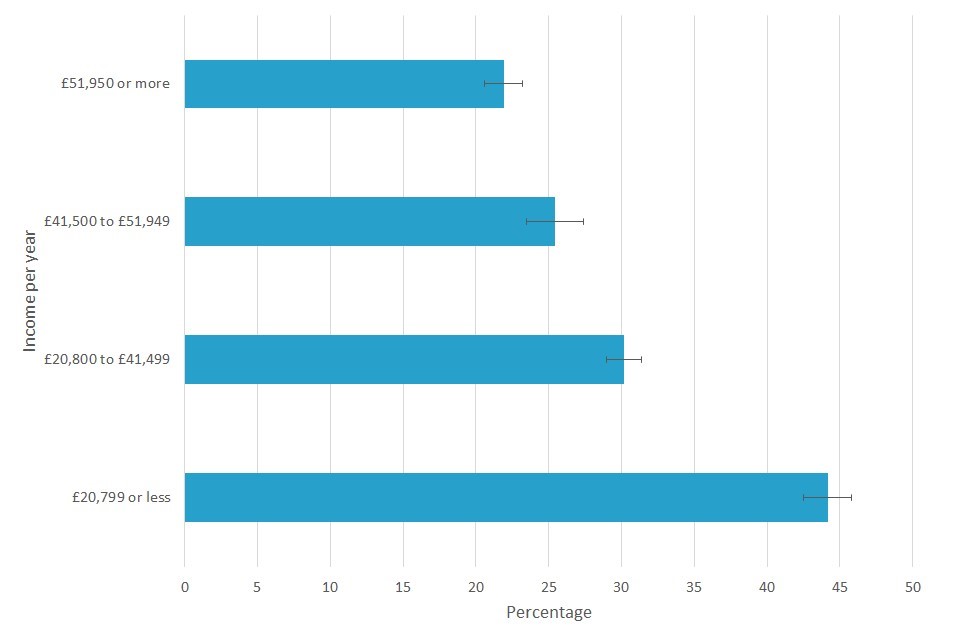

Income by money worries

UK veterans that agreed to some extent they had money worries in the last month were much more likely to say their income was £20,799 a year or less and less likely to say their income was £51,950 a year or more, than those who disagreed to some extent.

Figure 5: Veterans that said their income was £20,799 a year or less were most likely to agree to some extent that they had money worries in the last month

Weighted percentages of veteran responses about income by level of agreement they had experienced money worries in the past month, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked if in the last month, they have had money worries.

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked what their total personal income was over the last 12 months.

Because of small numbers or large confidence intervals, income was grouped into four categories to allow meaningful analysis of income by personal characteristics.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Types of loans and credit received since leaving service

UK veterans whose income was £51,950 a year or more were more likely to have received a mortgage since leaving service than those whose income was £51,949 or less. There were minimal differences in proportions receiving personal loans, credit cards and other types of loans by income.

UK veterans that said they agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the last month were much more likely to have received a personal loan (67.2% compared with 50.0%), credit card (77.9% compared with 70.1%) or other type of loan (14.3% compared with 8.7%) since leaving service than those that disagreed to some extent; they were less likely to have received a mortgage (68.5% compared with 81.5%).

Universal Credit, Personal Independence Payment or Adult Disability Payments

As expected, UK veterans whose income was £20,799 a year or less were more likely than veterans with a higher income to have claimed Universal Credit, a Personal Independence Payment or an Adult Disability Payment in the last month. Those whose income was between £20,800 and £41,499 were also more likely to have claimed Universal Credit, a Personal Independence Payment or an Adult Disability Payment in the last month than those earning £41,500 or more.

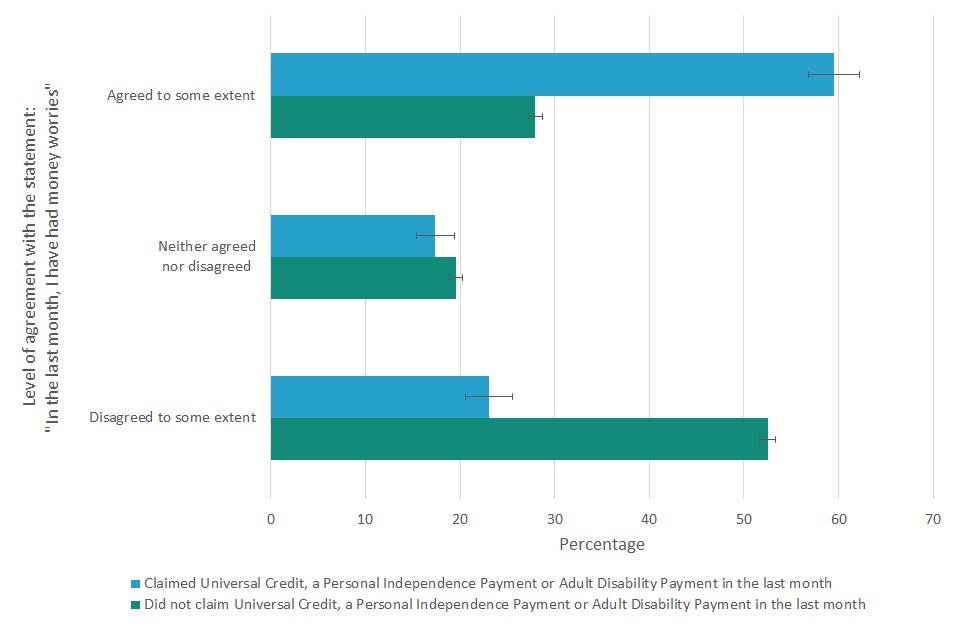

Figure 6: Almost 60 percent of veterans that had claimed Universal Credit, a Personal Independence Payment or Adult Disability Payment said they agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the last month

Weighted percentages of veteran responses about level of agreement they had experienced money worries in the past month by whether they had claimed Universal Credit, a Personal Independence Payment or Adult Disability Payment, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Blank responses and “Prefer not to say” responses were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.

Only veterans completing the survey on their own behalf (without assistance) were asked if in the last month, they have had money worries.

Personal Independence Payments and Adult Disability Payments are not means tested.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

Data for types of loans and whether a veteran was in receipt of Universal Credit, Personal Independence Payment or Adult Disability Payments by personal and service characteristics are available in our accompanying dataset. The footnotes also provide an outline of patterns seen in data for each of the four nations.

Rank

UK veterans that served at Officer rank were less likely to have said their income was £20,799 a year or less, or £28,800 to £41,499 a year, than those that served below Officer rank. Conversely, those that served at Officer rank were more likely to have said their income was £41,500 a year or more than those that served below Officer rank.

Those that served at Officer rank were less likely to have agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the last month than those that served below Officer rank (18.9% compared with 34.1%).

Preparedness to leave the UK armed forces

UK veterans that were unprepared to some extent for life after service in the UK armed forces were more likely to have said their income was £20,799 a year or less than those that were prepared to some extent (32.7% compared with 18.7%) and were less likely to have said their income was £51,950 a year or more (15.8% compared with 26.0%).

Those that were unprepared to some extent for life after service were much more likely to agree to some extent that they had money worries in the past month than those that were prepared to some extent (45.4% compared with 19.1%).

Housing

We are not able to publish data on income or money worries by housing tenure because of small numbers in some housing tenure categories of interest. In this section we consider housing tenure by personal characteristics and attributes. We particularly focus on housing tenure categories for which data from censuses are not available, for example, veterans living long-term with family or friends. We also focus on categories where there may be enumeration issues, for example, veterans that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse, as outlined in the Office for National Statistics’s (ONS’s) Housing quality information for Census 2021 methodology. Future analysis will focus on veterans that responded to the survey from prisons.

The majority (78.9%) of respondents said they lived in an owner-occupied or shared ownership house or flat, as reported in ONS’s Veterans’ Survey 2022, demographic overview and coverage analysis, UK article. A further 8.9% lived in privately rented accommodation and 6.0% lived in a socially rented house or flat. This is similar to the findings in our Living arrangements of UK armed forces veterans, England and Wales article.

The Veterans’ Survey 2022 had additional response options to this question, compared with the questions that were available for Census 2021. Around 9 in 400 (2.3%) veterans said they lived long-term with family or friends. Around 1 in 400 (0.3%) veterans said they were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse (these categories were combined because of small numbers in individual categories) and 3.7% said they had another living situation; veterans in a UK prison or a care home will make up some of this percentage.

Homelessness, rough sleeping, staying in a refuge for domestic abuse or living long-term with family or friends

Just over 1 in 10 (10.8%) veterans that were homeless or rough sleeping said they had received government support, such as from Veterans UK or their local council. Just over 1 in 20 (5.7%) veterans that were homeless or rough sleeping said they had received support from charities, such as Citizens Advice, Shelter or SPACES, to help with housing. Among the remaining responses, each reason proposed for not having received government or charity support was equally cited by respondents once we took uncertainty into account.

Reasons for not seeking support were:

- I was not aware of this support

- I am not eligible

- the support offered to me was not what I needed

- I do not need any support

- I do not trust the government/I do not trust charities

- other

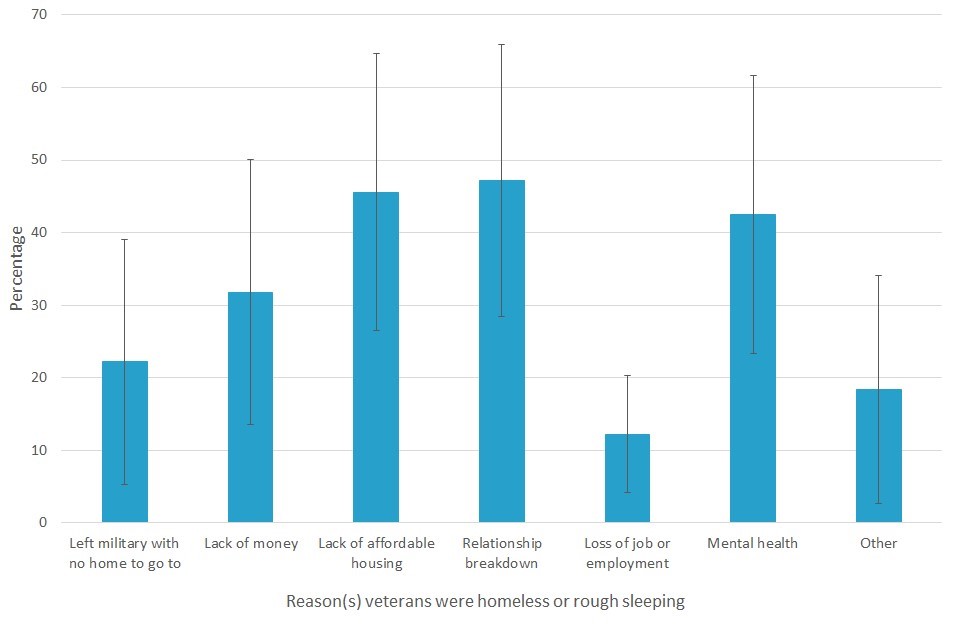

Respondents that said they were “Homeless (including sofa surfing)” or “Rough sleeping” were asked: “For what reason(s) are you homeless or rough sleeping?”.

Mental health, relationship breakdown or lack of affordable housing were more commonly cited as reasons for homelessness or rough sleeping than loss of job or employment.

Figure 7: Loss of job or employment was less commonly cited as a reason for veterans being homeless or rough sleeping than mental health, relationship breakdown or a lack of affordable housing

Weighted percentages of veteran responses about reason(s) why they were homeless or rough sleeping, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Respondents that were homeless or rough sleeping could select multiple responses to the question “For what reason(s) are you homeless or rough sleeping?”.

The response options “Left prison with no home to go to” and “Addiction” are not presented because of disclosure control.

Proportions may not sum to 100.

The Veterans’ Survey 2022 asked an open question: “Can you tell us what service and support would be helpful for you but is currently lacking?”. This question asked for free text, qualitative responses. These have been classified into high-level themes and can give some insight into what veterans may have meant by “other” as a response option to the reason for their homelessness. Each response could be classified to multiple themes, where applicable. Content analysis of responses is unweighted. Our approach to qualitative analysis is outlined in our Preparedness to leave the UK armed forces, Veterans’ Survey 2022 publication.

We discuss the most prevalent themes in responses from veterans that were rough sleeping, veterans that were homeless or sofa surfing and veterans that said they lived long-term with family or friends. Full descriptions for each theme are in Glossary: qualitative themes. This analysis uses the full sample of responses. We were unable to comment on veterans that were living in a refuge for domestic abuse.

Analysis of responses to what support veterans felt was lacking for those that said they were rough sleeping revealed only two themes. These were the housing support theme and a theme about feeling that no one cared about them. The housing support theme was not identified as a common theme when we assessed responses from veterans of all housing tenures.

Veterans that said they were rough sleeping said housing support was lacking and the majority of them felt that no one cared.

“Someone who cares about veterans, not some politician.”

“No one cares.”

The most prominent themes identified when considering veterans that were homeless or sofa surfing were the housing support theme and the health theme. The housing support theme was referenced by over half of these respondents. The health theme was referenced by around a quarter of respondents and the vast majority spoke specifically about mental health support. This suggests this is an important area of support that veterans in this group felt was lacking. Awareness of, coordination of and signposting to available help, finance support, career support, family support and transition were also prominent themes. These were often mentioned alongside or in conjunction with housing support and mental health support. You can read a full description of what veterans alluded to within each theme in Glossary: qualitative themes.

Veterans that said they were homeless or sofa surfing said housing support was lacking and referenced a lack of support for veterans in relation to health and mental health most prominently.

“Correct housing, not with civi drug addicts, alcoholics, smokers.”

“Military trained mental health services.”

“Timely mental health assistance.”

“I am too ashamed to admit I can’t cope.”

The most prominent theme among veterans that were living long-term with family or friends was the health theme, which was referenced by around a third of these veterans. Around half of these responses specifically pointed to mental health support. Career support and awareness of, coordination of and signposting to available support were the next most prominent themes for veterans that said they lived long-term with family or friends.

Around 1 in 10 referenced the lack of housing support or finance support.

Veterans that said they lived long-term with family or friends most frequently said health support and mental health support was lacking and referenced a lack of support for veterans in relation to signposting to available services and careers information.

“It’s a bit late, I should have received help when I left the Army. I was medically discharged and left to my own devices. I had no idea what to do, where to go for further help. So, like most ex-military, I buried my issues deep within only for them to consequently ruin my life further down the line.”

“Sheltered housing opportunities for veterans with poor health and/or mobility issues. Many of these late developing issues are service related.”

“In desperate need of better healthcare to quickly resolve a physical health issue which has left me out of work with zero income, causing further degradation of my mental health.”

“Should be kept in contact with organisations that are easy to get answers for any situation when required and not be left to sort things out on your own.”

“Advice on transferring into different sectors away from traditional roles when leaving the military. It’s been difficult finding any information about moving into the Charitable sector and what level I could join in at and so, because of that, I’ve felt like I had to join from the bottom.”

Previous experiences of homelessness, rough sleeping and sofa surfing among veterans

Through our qualitative analysis of responses to what support veterans felt was lacking, we were able to identify veterans that were not currently homeless, rough sleeping or sofa surfing, but had talked about personal experience of this in their own past or current threat of this. It is important to note this analysis includes responses from veterans about homelessness regardless of how long ago they left the UK armed forces, and we are unable to decipher how long ago the experiences they refer to occurred. Policies directed at helping veterans and supporting homelessness in general have changed over time and have been directed at addressing some of the content within these themes. For example, in 2024 regulations were laid to exempt all former members of the regular armed forces from any local connection tests for social housing applied by local councils in England. The main themes identified among these responses are outlined in this section.

Local councils should have been able to do more for veterans and thresholds/guidance used for prioritisation of housing support seemed unfair to veterans.

“When I was discharged as a single soldier, I was homeless at the immediate point of discharge, and when I sought help I was told as a single male with no dependants I had no entitlement to accommodations just to wait and to go to citizens advice as I had been medically discharged with 30% disability this had a profound effect on my mental health and exacerbated my PTSD.”

“I’ve spent the past 5 years moving round from place to place, renting rooms and having no permanent address to live at. The waiting lists for Council housing are huge and rented accommodation prices are massive. There seems to be a total lack of any priority for ex forces when it comes to housing.”

“I was a single parent having completed a full service in the regular army and they would not even put me on the housing list they said I would be lucky to get emergency bed and breakfast and my son may not necessarily be accommodated with me. I felt like a piece of trash that they did not know what to do with.”

“Having found myself in need of a home I was made aware that if you leave the local area for 6 years you lose eligibility for housing. That surely cannot be right when service personnel enlist.”

“When I left the Army, I was homeless due to growing up in care and when going to my local council they would not declare me as homeless there as I did not have family in the area and said I had to go to a different council even though they would say the same. I had to spend time on the street until I could get job seekers and housing benefit to get in a hostel.”

Better sign posting to housing support services before and after transition, ensuring veterans were more prepared upon leaving.

“In my experience it would have been helpful to have contacts and/or support on exit from the army around housing. I was medically discharged and had to sleep on my 12-year-old nieces bedroom floor for 6 months. I was not told about any services that would have been able to help me find somewhere to live.”

“I was given no info before leaving on what to do about housing even though my officers knew I had no family, and I was not aware before time that that would have been an issue.”

Connecting different services for a more integrated approach, particularly housing and mental health and health services.

“I am under threat of homelessness and with a service that only do clinical support for mental health. My therapy is in hold because of my accommodation situation. It reminds me of being on humanitarian operations – you get government agencies sticking to their defined roles and NGOs charging around doing their own thing in different directions and leaving the injured more confused.”

Veterans that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse and living long-term with family or friends by personal characteristics and service-related factors

This section includes breakdowns by personal characteristics and service-related factors for veterans that were:

- homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse

- living long-term with family or friends

This article focuses on UK-level data only, which are outlined in our accompanying datasets.

Homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse by personal characteristics and service-related factors

When we considered veterans that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse, there was no evidence of a difference in the proportion of veterans within this tenure group by sex, disability status, sexual orientation or economic activity status. Patterns by age were difficult to discern because of high levels of uncertainty.

Veterans that said they agreed to some extent they had money worries in that last month were more likely to be homeless or rough sleeping than those that disagreed to some extent (0.5% compared with 0.1%). Veterans that disagreed that they belonged to their local community to some extent were more likely to be homeless or rough sleeping than veterans that agreed to some extent (0.9% compared with 0.1%). Among veterans, there were no notable differences in awareness of housing support from Veterans UK by housing tenure. Those that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse, or those who said “other” to the housing tenure question (6.0%), were more likely to have used this service than those living in owner-occupied properties (0.6%) or those living long-term with family or friends (1.3%), but not more likely than those who lived in privately or socially rented property.

Veterans that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse or said “other” to the housing tenure question, were more likely than those of any other tenure to be aware of housing support by local councils, but not the most likely to have used these services.

Our accompanying dataset includes data at the UK-level for awareness, use of and satisfaction with housing support via Veterans UK and housing support via local councils not discussed in this article. Data on awareness of and satisfaction with these services by personal characteristics and service-related factors are also provided.

When we considered service-related factors, there was no evidence of a difference in the proportion of veterans that were homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse by:

- service branch or type of service

- years since leaving service

- rank

- reason for leaving

- deployment

- witnessing or taking part in enemy operations

- experience of bullying, discrimination or harassment during service

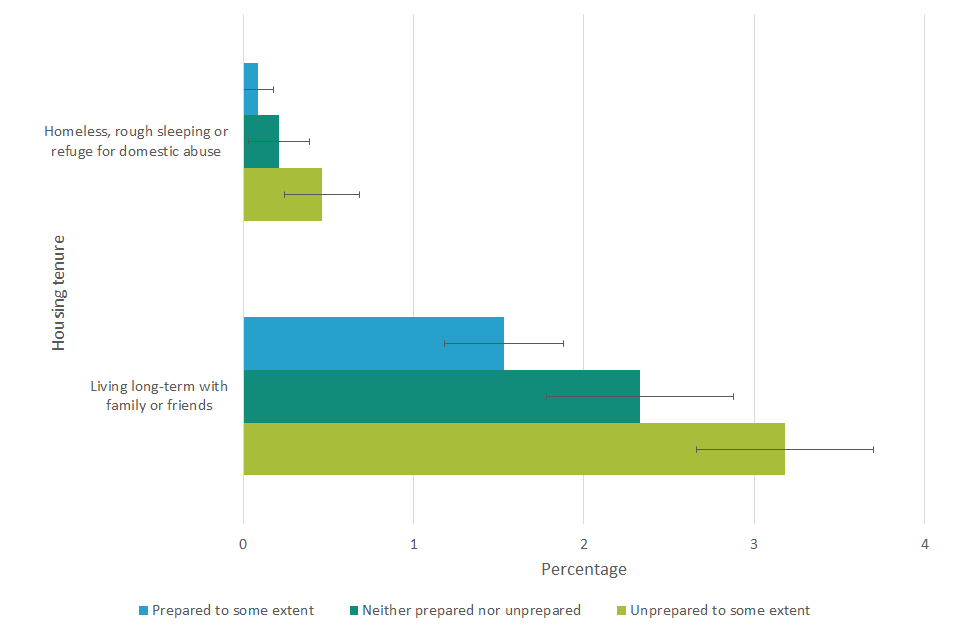

However, veterans that felt unprepared for life after service to some extent were more likely to be homeless, rough sleeping or living in a refuge for domestic abuse than veterans that said they felt prepared to some extent (0.5% compared with 0.1%).

Living long-term with family or friends by personal characteristics and service-related factors

Those UK veterans aged 18 to 29 years were much more likely than any other age group to be living long-term with family or friends. Those aged 18 to 49 years were more likely to have reported this living arrangement than those aged 50 years and over. This was not unexpected, given that increasing numbers of young adults are living with family in the general population, as outlined in the Office for National Statistics’s (ONS’s) Census 2021 report More adults living with their parents.

There was no evidence of differences in the proportion of veterans living long-term with family or friends by sex, disability status or sexual orientation. Those that were economically active were more likely to be living long-term with family or friends than those that were not (3.1% compared with 1.5%). This is expected given the younger age profile of veterans living long-term with family or friends. Those who agreed to some extent that they had money worries in the last month were also more likely to be living long-term with family or friends than those that disagreed to some extent (3.5% compared with 1.4%). Veterans that said they disagreed to some extent with the statement “I feel like I belong to my local community” were more likely to have reported this living arrangement than those that agreed to some extent (4.8% compared with 1.2%).

When we considered service-related factors there was no evidence of a difference in the proportion of veterans that were living long-term with family or friends by:

- service type

- service branch

- reason for leaving

- deployment

- witnessing or taking part in enemy operations

- experience of bullying or harassment during service

However, veterans that had served below Officer rank were more likely to be living long-term with family or friends than those that served at Officer rank (2.7% compared with 1.2%). Veterans that had served less than 5 years were also more likely to be living long-term with family or friends than those that had served for longer periods. Veterans that felt unprepared for life after service to some extent were more likely to be living long-term with family or friends than veterans that said they felt prepared to some extent (3.2% compared with 1.5%).

Figure 8: Preparedness to leave the UK armed forces had a relationship with whether veterans were living long-term with family or friends or were homeless, rough sleeping or staying in a refuge for domestic abuse

Weighted percentages of veteran responses about preparedness to leave the UK armed forces by housing tenure interest groups, Veterans’ Survey 2022, UK.

Source: Veterans’ Survey 2022 from the Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Blank responses and “Prefer not to say” responses were removed from this analysis because of high levels of uncertainty.